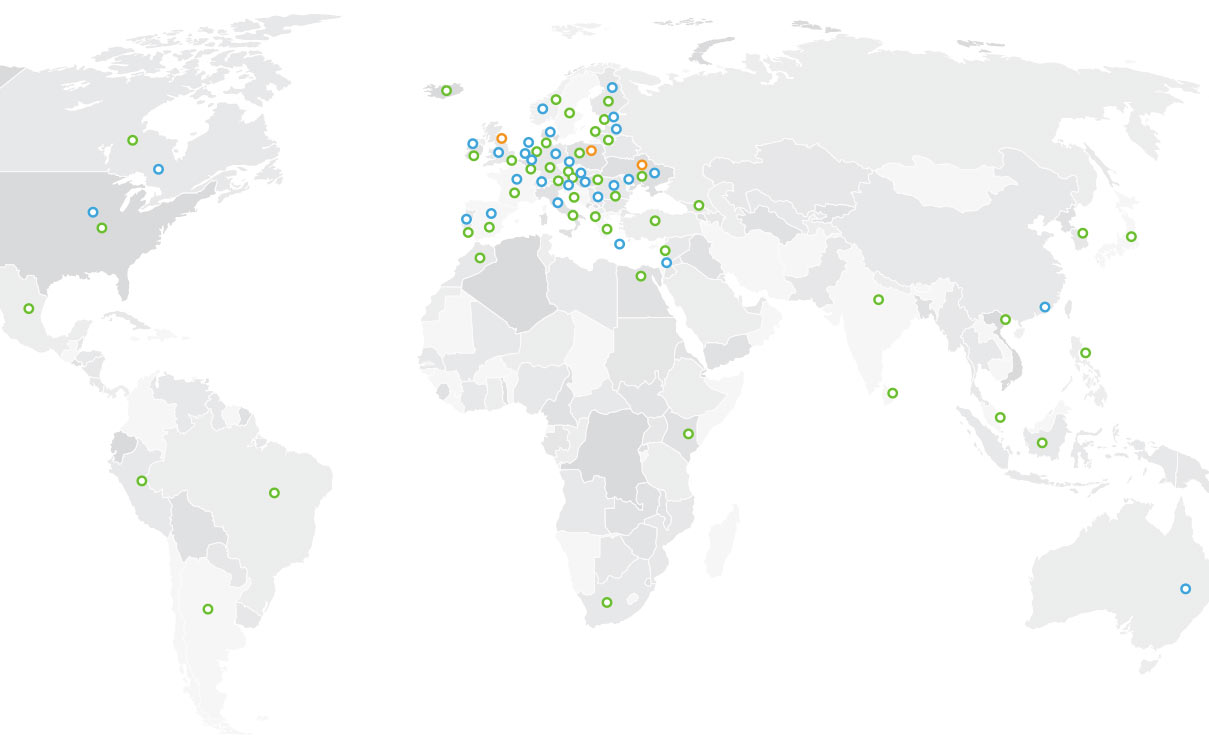

With vast experience in providing translation, localisation, and transcreation services to businesses worldwide, we have native expertise in major European markets, including Ukrainian, Polish, and British. This expertise allows us to provide translations that sell. Renowned marketing companies such as Adapt WorldWide (Welocalize company), Ogilvy, Havas Digital and Havas Engage, Promodo, Dozen, and many more have entrusted us with their high-profile projects.

50+

At Translators Family (TF), we offer a full range of translation and content creation services in more than 50 languages, including:

Arabic, Bulgarian, Chinese, Czech, Danish, Dutch, English, Estonian, Farsi, Finnish, French, Georgian, German, Hebrew, Hindi, Hungarian, Icelandic, Indonesian, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Latvian, Lithuanian, Malay, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Slovak, Slovenian, Spanish, Swahili, Swedish, Russian, Tagalog, Tamil, Tibetan, Turkish, Ukrainian, and Urdu.

Trusted since 2006 by:

OUR TRANSLATION COMPANY THIS YEAR

![]()

3,000 clients

![]()

1,000 linguists

![]()

3 locations

We help businesses and governmental/non-profit organisations worldwide communicate effectively by providing custom multilingual solutions.

14M words

TRANSLATED

1,000 hours

INTERPRETED

over 50

LANGUAGES

OUR SERVICES

Flexible translation solutions for your multilingual projects

Two pairs of eyes to perfect your message

A cost-effective solution: machine translation with human editing

Expand your online presence, reaching new markets

Consecutive and simultaneous conference interpreting (oral translation)

Preparation and formatting of your documents for publishing

AI content + a human touch = cost-effective and quick results

Creation or adaption of multilingual content that sells

Elevation of your online presence with search engine optimisation

Connect, engage, and grow your business across borders

Creation and localisation of subtitles, ensuring precise timecoding

Giving your content a global voice

INDUSTRIES WE TRANSLATE FOR

Leveraging our extensive network of specialist IT translators, we utilise cutting-edge technical tools and knowledge to localise all necessary elements of IT projects expertly. Trusted by several IT companies and start-ups, including Indigo and Loud Beings, our services cater to their linguistic needs and enable expansion into new markets.

With a rich project history in various engineering fields, particularly manufacturing, automotive, energy, and mechanics, we offer a comprehensive range of services, such as translation, desktop publishing (DTP), machine translation (MT) post-editing, and other localisation services. Large engineering companies, including BorgWarner (formerly Delphi Technologies), have trusted our expertise to meet their linguistic requirements.

We have translated over 15,000 pages of technical documentation for leading automotive provider BorgWarner (formerly Delphi Technologies) and provided interpreting services throughout one-year training courses for their engineers at the Hungarian factory. Other prominent automotive companies we have worked with include Honda Motors, BMW, and Skoda.

We demonstrate our respect for these domains through careful attention to detail and a high degree of specialisation, ensuring thorough quality control. We have experience translating projects in the fields of medical equipment, pharmaceuticals, dentistry, clinical trials, and healthcare.

Our vast experience includes a four-year contract with the European Parliament to provide translation services. Additionally, we have successfully handled large volumes of translation projects for well-known organisations, such as the UNHCR (with a 2-year contract won via tender) and the FAO. Many non-profit organisations, including Vital Voices, the Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights in Poland, and REACH Ukraine Crisis, have entrusted us with their linguistic needs.

Thanks to our multi-step quality control systems, we have successfully delivered fluent and flawless professional texts for numerous large educational organisations and companies, including EF Education First and WSZiB (the School of Management and Banking in Krakow). Our commitment to creating beautifully written content ensures the highest quality for all projects in this domain.

We ensure that only specialist legal or financial translators work on content with specific implications. Additionally, we offer sworn translations in Poland and notarised translations in Ukraine. Our clients include law firms (e.g., OK Capital), financial institutions (e.g., Eastern Wires), chambers of commerce (e.g., the Polish-Dominican Chamber of Commerce), and many others.

Call or email us today!

We speak your language

Phone

Call our Polish office (most likely Ada will reply you):

+48 222 302 512

(autoresponder will try to answer your questions first) or

+48 792 447 724

(human conversation right away).

Call our UK office (you'll get in touch with Oleg):

+44 757 898 17 92.

You can also use WhatsApp, Telegram, and Viber to contact us.

Please remember that our work hours are 9 am to 5 pm CET (10 am to 6 pm GMT).

Translators Family Poland: Warsaw, Marszałkowska 58, 00-545.

VAT: PL5252611421

Translators Family UK: Stuart House, Eskmills, Musselburgh, EH217PB

Get a Quote

It will only take 5 minutes of your time

By using this form you agree with the storage and handling of your data by this website and Translators Family.

Legal information: This is a non-binding quote. All information submitted, including your name and email address, will be kept confidential and will not be shared with any third party. Please be advised that, in accordance with the binding EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), Translators Family processes your personal data based on Article 6, par. 1 (b), i.e. when processing is necessary for the performance of a contract to which the data subject is party, or in order to take necessary steps at the request of the data subject prior to entering into a contract. In this case, this refers to providing our quotation and translation services at your request. You can always request to withdraw your data sending us your email to info@translatorsfamily.com. The administrator of your personal data is Translators Family. Read more in Privacy Policy